On view in the Gelman Gallery through January 28, the exhibition provides a snapshot of the student experience in each of RISD’s 16 undergraduate departments.

First Comprehensive Nancy Elizabeth Prophet Exhibition Now Open at RISD Museum

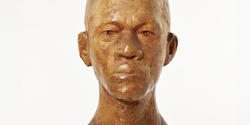

One hundred and six years after Nancy Elizabeth Prophet graduated, the RISD Museum is exhibiting the first major presentation of her work, including sculptures, watercolors, tools and photographs. Prophet, a native Rhode Islander who majored in freehand drawing and painting with a concentration in portraiture, was one of the first known women of color to graduate from RISD, a sculptor and a member of the expatriate artistic community in interwar Paris.

Nancy Elizabeth Prophet: I Will Not Bend an Inch is curated by Sarah Ganz Blythe, deputy director of exhibitions, education and programs; Dominic Molon, Richard Brown Baker Curator of Contemporary Art; and Kajette Solomon, social equity and inclusion specialist. The exhibition, which contains all of Prophet’s known work, will be on view through August 4, 2024.

“The RISD Museum is fortunate to hold the largest collection of Prophet’s work,” says Ganz Blythe, "and this is the most comprehensive presentation of her oeuvre to date. It is fitting that her first solo show—something she talked about in her writings—is presented here, where she would have studied before completing her degree in 1918.”

“Nancy Prophet was born in Rhode Island to a Narragansett father and a Black mother, and it was important that we honor both parts of her heritage.”

Solomon adds, “Nancy Prophet was born in Rhode Island to a Narragansett father and a Black mother and it was important that we honor both parts of her heritage. In planning for the show, we hosted two community gatherings and consulted with local institutions. These conversations resulted in a deeper understanding of her work and even the inclusion of additional pieces, such as Peace, a carved and painted relief on loan from the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society.”

The exhibition’s title comes from Prophet’s diary, which is also on display. Her personal writing, along with her correspondence with W.E.B. Du Bois, the African American historian and civil rights activist, is crucial to understanding her sensibility as a female artist of color working in a world of entrenched racism and sexism.

“In her writing, we see that Prophet felt a deep spiritual drive, something within her that said, ‘I have to make, I have to create. I have no choice,’” says Solomon.

The show traces Prophet’s creative output from her 12-year stay in Paris, where she enrolled in the women’s sculpture studio at the École des Beaux-Arts, to her move to Atlanta in 1934 to co-found the art department at Spelman College and her return to Rhode Island in 1944. The comprehensive exploration of Prophet’s oeuvre helps viewers to consider her work in a global context, says Molon.

“Prophet’s RISD training comes through in her appreciation of classical forms and dedication to precision and formality,” Molon adds. “But her modernist sensibilities appear in the rough-hewn quality of her sculptural bases and her open-ended titles that suggest states of being rather than a faithful portrait likeness. As contemporary art sees the rise of African American figurative art, Prophet’s work continues to resonate.”

The exhibition includes Congolais, a sculpture inspired by her attendance at the Paris Colonial Exposition, a six-month exhibition of art and objects from France’s colonial holdings. Now critiqued as an attempt to justify French colonialism, the exhibition excited Prophet, who wrote about the importance of seeing a large display of African art. Other pieces that speak to Prophet’s global cultural engagement include Head in Ebony, a sculpture that established her presence in the Paris art world and was later owned by Du Bois, and Head of a Cossack, thought to be inspired by a Turkish leader frequently covered in international media.

Bringing together all known Prophet works was a challenging endeavor made possible by community collaboration. In addition to the piece on loan from the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, museums, archives and private collectors loaned works to appear in the collection. Community members provided insights that informed the exhibition.

“As contemporary art sees the rise of African American figurative art, Prophet’s work continues to resonate.”

Photographs of Prophet’s Paris studio, on loan from Rhode Island College, show works that have been lost or destroyed, demonstrating the breadth of her output and the possibility that yet more works may be recovered. The show’s curators hope that the exhibition itself will unearth more Prophet work held in private collections.

Nancy Elizabeth Prophet: I Will Not Bend an Inch will travel to the Brooklyn Museum and the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in 2025. The exhibition is complemented by a book by the same name, published by Yale University Press and co-edited by Ganz Blythe, Molon and Solomon. The book includes contributions from contemporary artists Simone Leigh and Kelly Taylor Mitchell MFA 18 PR and a conversation between Tomaquag Museum Director Lorén M. Spears and Narragansett historian Mack H. Scott III.

Lauren Rebecca Thacker / top image: Negro Head, ca. 1924

February 26, 2024