A jury of professional illustrators and art directors selected the winning pieces out of more than 4,000 entries.

Art, Archeology and Scholarship Converge in Spring RISD Illustration Course

Students in a spring Scientific Illustration course taught by longtime Illustration Professor Jean Blackburn 79 PT are working directly with scientists and scholars, learning how to create visually compelling drawings that clearly convey complex information. After honing their skills drawing natural specimens in RISD’s Nature Lab and Special Collections in the Fleet Library, they met with noted archeologist Andrew K. Scherer, a Brown University researcher studying Maya communities that flourished along the Usumacinta River in southern Mexico and Guatemala between 400 BC and 900 AD.

“It’s so important for students to learn how to communicate and work with science professionals,” says Blackburn. “The course is intended to help them develop a deep understanding of scientific illustration, including historical traditions and contemporary advances in the field.”

About midway through the spring semester, Scherer visited the class to answer questions about the various sites students will help to interpret with their illustrations, notably the capital city of Piedras Negras (Black Stones), which was home to 3,000–4,000 people at the time. Scherer’s research focuses on the bones and other materials unearthed on-site and what they can tell us about the Mayas’ lives—everything from ritual practices and warfare to diet, community values and creative practices.

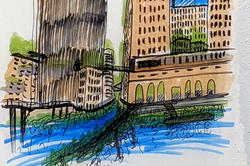

“Today we want to establish the blocking in of the spaces Andrew would like illustrated,” Blackburn explained as the session began. “Since these are all reconstructions, establishing the viewer’s point of view is essential. What’s in the background? What is the time of day and quality of light? In addition to the landscape and architecture, consider what types of activities would be taking place in your scene.”

Several students are drawing the Piedras Negras marketplace, using images from the murals of Calakmul discovered in modern-day Campeche, Mexico to inform the clothing and activities they will feature in their drawings. “Aside from the exchange of goods,” Scherer noted, “we also know people in the marketplace were crafting objects, visiting sweat baths, making offerings at a small pyramid and having their teeth pulled. In terms of architecture, all of the buildings had white stucco finishes and thatched roofs, and most had awnings that could be pulled out for shade.”

A second group of students is focusing on the nearby beach, where canoes crossing the river with goods for the marketplace were loaded and unloaded. Scherer advised them to consider the river’s water level, which changed dramatically between the dry season and the wet season, and to remember that all of the goods were hauled in bundles.

“Today, there are crocodiles in the river,” he added, “but Mayas probably ate them. There were tons of iguanas and birds—toucans, macaws, etc.—and domesticated animals like dogs and ducks. You might show people fishing in the river using lines or nets, both of which were common.”

Another body of water the students are attempting to bring to life is Agua Cristalina (Crystal Clear Water), which is located along the Busilha River. The site maps and lidar images Scherer shared with the class show two nearby pyramids, a sculptural stela (or upright stone monument) and a large space that might have been used for performances or bloodlettings, which are believed to have been a way for Mayas to communicate with the gods.

“This project requires research as well as compositional and conceptual dexterity,” Blackburn reminded the class. “The horizon line is really important, and you can use vanishing points to draw the eye and engage the viewer. Remember that your illustration is telling a story.”

Top image: an interpretive drawing in progress by senior Lucinda Drake depicts ancient Mayas at the market.

Simone Solondz / photos by Kaylee Pugliese

April 28, 2025